Islands (Scotland) Bill: More Than Shetland Out Of The Box?

Date: 11/06/2018 | Construction, Energy & Natural Resources, Environmental, Real Estate

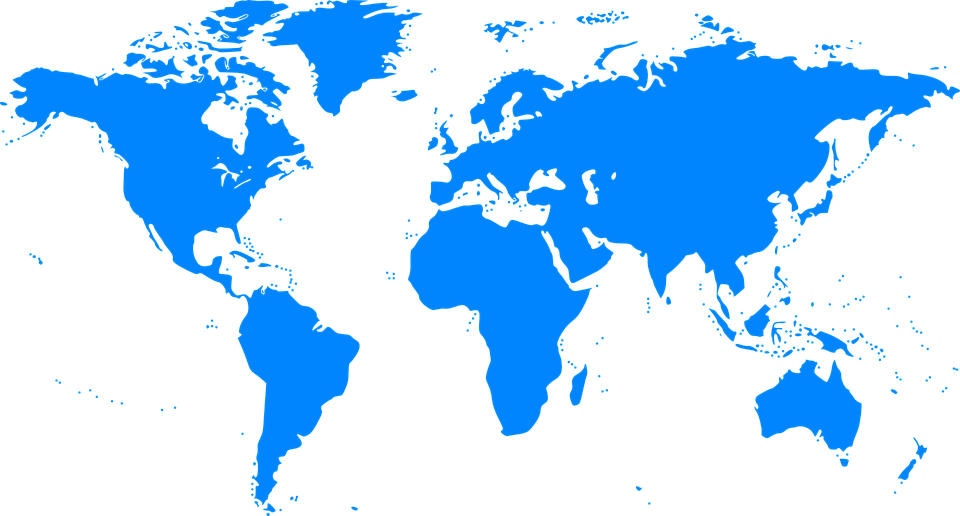

The Islands (Scotland) Bill passed Stage 3 of parliamentary scrutiny on 30 May 2018. The light-hearted media coverage of how Shetland must be depicted on maps of Scotland (“no-one puts Shetland in a box!”) belies a more serious Scottish Government objective: to highlight the distinctive features of the islands and improve outcomes for their communities.

The Bill introduces new requirements for how public functions are carried out, providing for increased representation of island communities, devolution of public functions and the creation of an island-specific marine licensing regime. As such, it has potentially significant ramifications for development planning and all parties involved in it.

As with most planning matters, the devil is in the detail and a meaningful assessment of the Bill’s implications will not be possible until regulations, guidance and best practice notes are issued in support of the reforms. In the meantime, we have examined the key features of the Bill and what questions they pose for developers, planning authorities (“PA”s) and island communities alike.

National Islands Plan

Six of Scotland’s thirty-two PAs wholly or partly cover islands (Orkney, Shetland, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar/Western Isles, Highland, Argyll & Bute and North Ayrshire). PA jurisdictions generally include “land” and extend down to the Mean Low Water Mark (“MLWM”). Scottish Ministers are responsible for marine planning from Mean High Water Mark out to 12 nautical miles out to sea (“NM”). Until now, this jurisdictional overlap has been addressed by marine and terrestrial plans being required to take one another into account. The Bill seeks to amplify this obligation to co-operate by placing a duty on the Scottish Ministers to prepare a National Islands Plan (“NIP”) which would, among other effects, inform future planning decisions.

The first draft NIP is due within a year of the relevant part of the Bill coming into force but there is no real detail on what the NIP should include. The Bill simply requires it to set out strategies for a relevant authority carrying out functions of a public nature which affect the islands. These public functions cover population increases, sustainable development, environmental well-being, health and wellbeing, community empowerment, transport services, digital connectivity, fuel poverty, management of the Crown Estate and biosecurity (including protection from invasive, non-native species).

So far, so strategic, but what will it mean for developers seeking consent on the islands? As a statutory document, the NIP is likely to be a material consideration in planning decisions but it is not clear how the NIP will fit into the planning framework (as it currently stands and as subject to reforms under the emerging Planning Bill).

Representing Island Communities

The Bill creates a new class of stakeholder, the “island community”, to which public bodies must have regard and produce an impact assessment where it appears a “policy, service or strategy is likely to have an effect on an island community which is significantly different from its effect on other communities” in the same PA administrative area (Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee, Stage 1 Report on the Islands (Scotland) Bill, 2nd Report 2018 (Session 5) at para 135).

This provision is wide-ranging and also requires the Scottish Government to consider and consult with island communities when exercising its powers. In some cases it may even be requested to retrospectively assess the impact of existing legislation on island communities.

To further protect the representation of island communities, the Bill secures the boundaries of the constituency of Na h-Eileanan an Iar (Western Isles) and provides for the review of wards in local government areas. It also enables the devolution of additional powers to island PAs from the Scottish Government. The manner and substance of such devolution will become clearer once relevant regulations are published, required within a year of the Bill being enacted.

Pending the draft regulations and other guidance, these features of the Bill relating to island representation, again, raise questions. What exactly is an “island”? What is a “community”? Although some definitions are included in the Bill, unless and until they are tested in the Courts, they could lead to protracted debate. The question also remains as to what additional powers island PAs might seek, to which Part 5 of the Bill may offer some answer.

Island Marine Licence

Part 5 of the Bill empowers the Scottish Ministers to make regulations for a new licensing regime for marine areas adjacent to an inhabited island and up to 12 NM out to sea, measured from MLWM. The administration, granting and enforcement of such licences would be one of the additional powers passed on to island PAs (and run alongside the PAs’ existing terrestrial powers under the Town and Country Planning regime). Although the Bill envisages the regulations will provide for application fees to be charged by the PAs, it is not yet known if there will be an increase in PA funding to deal with Island Marine Licences (“IML”s) more generally. The new IML regime would apply to “development activity”, which is broadly defined as “(a) construction, alteration or improvement works of any description (either in or over the sea, or on or under the seabed), (b) any form of dredging” (Section 16), but generally excluding oil, gas, defence, fishing and fish farming.

All stakeholders will be eagerly awaiting further information in the new regulations about how IMLs will interact with other consenting regimes, such as Marine Licences under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 or consent under Section 36 Electricity Act 1989 (to construct generating stations). This is particularly the case given penalties for breaching the licensing rules include a maximum fine of £50,000 and/or imprisonment for a maximum of 2 years.

Next Steps

Timescales for passing the Bill into law are unclear but, with Parliamentary recess fast approaching at the end of June, this is likely now to be towards the end of 2018 (if not later). When the Scottish Government starts to consult island PAs on the regulations to be made under the eventual Act, it will bring into sharp focus whether the additional powers so desirable in theory can really be exercised in practice in a public sector already under strain.

If you would like to discuss any of these issues, please contact Jacqueline Cook